Commentators such as Jon Faine on ABC Melbourne have pointed out that previous attempts taken in Victoria to independently investigate police were unsuccessful.

But are these previous attempts an indication that it would never work? What can we learn from these previous attempts to keep police accountable in Victoria?

A study by Dr Ian Freckelton QC described how a genuinely committed civilian review authority in Victoria, the Police Complaints Authority or “PCA” ultimately failed.

The example of the Victorian Police Complaints Authority highlights the importance of getting culture, resources, complainant involvement and enabling legislation right from the beginning.

The Police Complaints Authority operated between 1986 to 1988. It had only seven staff members and was headed by Hugh Selby. The PCA’s willingness to act was evidenced by its complainant focused attention to investigation. It operated a 24 hour complaint hot-line and was willing to travel to complainants. It was also willing to exercise its power to investigate “public interest” complaints and saw these as including complaints made by ordinary people about police abuses. It conducted thorough re-investigation of complaints where complainant’s raised concerns about the initial police investigation.

It also had a high media profile commenting on trends and issues relating to police misconduct.

Some senior Victoria Police still recall with bitterness the Police Complaints Authority’s plans to make themselves accessible to potential complainants in a suburban pub. The Police Association at the time were furious, sought an injunction, accusing the Complaints Authority of ‘touting for business’. (There has been virtually no outreach into communities impacted by police violence by any of the oversight bodies in the decades since.)

Unfortunately the PCA was seriously under funded by the Government and hampered by badly drafted legislation. You can sense the frustration in Mr Selby’s first Annual Report in 1987 after sixteen months diligently investigating cases, reporting to Parliament and proposing enhanced legislation for the proper handling of complaints.

“There have been several attempts to make this publicly funded body quite ineffectual.” Mr Selby writes. “First there was a program to bury this office in forests of paper while providing absolutely no useful information. It was to be a phony war in which the PCA would become a terminal case of bureaucratic paper shuffling. Any attempts by this office to seek facts were politely, but firmly rebuffed. The great attractiveness of this tactic was that at all times its prosecutors could correctly assert that they were acting strictly in accordance with the legislation: the classic “work to rule” approach.”

It was almost as it was set up to fail. Despite clear attempts to establish co-operative relationships with police and a clear mandate to improving the level of public confidence in our police force, assist the police to improve the quality of police practices and procedures, it was consistently attacked and undermined by the Police Association at the time.

It was shut down by the Government within two years of its commencement.

The example of the Victorian Police Complaints Authority highlights the importance of getting culture, resources, complainant involvement and enabling legislation right from the beginning.

This reflects concerns about the failures of some international models which are not provided with adequate powers or resources and the problems being highlighted with the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC) in NSW.

The model currently being considered by the joint parliamentary IBAC Committee is a body separate from police that can independently investigate complaints made against police.

The role could be conducted by IBAC with some significant legislative and cultural changes, which would include the quarantining of a dedicated specialist, police focused investigative unit, separate from teams that carry out anti-corruption investigations.

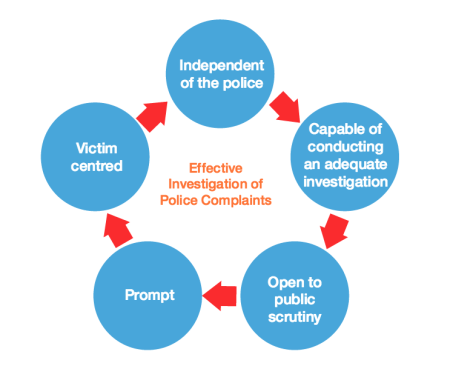

The body must be properly resourced and empowered to meet the standards required of police oversight and accountability, established by the European Court of Human Rights:

• Independent of the police (institutionally, culturally, and politically);

• Capable of conducting an adequate investigation (i.e. an investigation leading to criminal and/or disciplinary outcomes);

• Prompt in its investigations;

• Open to public scrutiny;

• Victim centred; enabling the victim to fully participate in the investigation, including through access to

information relevant to their complaint.

The old Police Complaints Authority did not meet these benchmarks. It tried but was never able to.

But Victoria needs to move away from the ‘review’ model which replaced it – under which police retain responsibility for formal investigations into misconduct complaints and deaths caused by police.

Such models have consistently failed to deliver public trust and meet human rights benchmarks and is currently failing Victoria.

It’s not the eighties anymore. We need a modern, well resourced and world class police accountability system – with more than seven staff.

See more at: Independent Investigations of Police Misconduct

References:

Freckelton, Ian 1991 “Shooting the Messenger” in Complaints Against the Police, The Trend to External Review, edited by Andrew Goldsmith.

Stakeholder Perspectives on Police… (PDF Download Available). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29456333_Stakeholder_Perspectives_on_Police_Complaints_and_Discipline_Towards_a_Civilian_Control_Model [accessed May 16 2018].

“Scandal, Inquiry and Reform” in Civilian oversight of Police, Prenzler, Heyer, Garth (2015) p 6.

“So few complaints are sustained after police investigation that one must conclude that either this State is populated by an extraordinary number of people willing to make false complaints about police or that there is something fundamentally wrong with internal investigatory methods.”

– Police Complaints Authority Annual Report 1986-87