The Victorian Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) recently released its review of Victorian police complaints investigation, the Audit of Victoria Police complaints handling systems at regional level (October 2016) The report makes a series of recommendations, for which our summary analysis and position is detailed below.

The Police Accountability Project of the Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre identifies that there are significant gaps and systemic issues that remain either unaddressed by the report, or that the recommendations do not sufficiently cover. This includes fundamental issues about inherent bias, low substantiation rates of meritorious complaints, complainants being ‘locked out’ of the complaints process, and lack of public trust and confidence in the complaints process as a whole. Whilst we broadly support these IBAC recommendations, they are purely limited to procedural issues within the existing complaints process and therefore do not address key concerns raised by our clients.

As such, this IBAC review does not adequately address the embedded integrity, transparency and independence issues with the current police complaints system.

Further, as the audit was conducted by IBAC itself, the limitations of IBAC as an agency were not tackled in the audit process. This includes issues of regulatory capture, whereby IBAC takes the view that that the vast majority of police misconduct complaints can be resolved at the station level. Currently IBAC has the resources and power to investigate a very small number of complaints against police. As it stands, complaints including those alleging excessive force or serious mistreatment by police are routinely investigated internally by line managers within Victoria Police, which does not reflect public interests or international human rights standards[1]. Further, IBAC processes are not transparent to the public or complainants. Pursuant to s194 of the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission Act (the IBAC Act), any complaint investigation made by Victoria Police following a referral from IBAC is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act 1982(the FOI Act). This is, as IBAC itself states, a broad exclusion. We believe it unreasonably removes a key avenue by which complainants can understand how their complaint was investigated.

The current police complaints system in Victoria is rife with issues concerning lack of accountability, transparency and independence. To address the persistent and recurring problems with Victoria’s police complaints system, rather than a series of minor reforms to the existing process for Victoria Police complaints handling systems at regional levels, the entire complaints system must be overhauled – primarily to move to independent investigation. More information about this may be found in our Independent Investigation of Complaints against the Police: Policy Briefing Paper.

Inherent bias in the investigation process

Firstly, while IBAC reviewed some Victoria Police files and made recommendations on 36% of these, the review makes no mention of inherent bias in investigations.

Extensive analysis by Community Legal Centres demonstrates that bias in the investigation is a regular problem in police complaints processes. In FKCLC’s “Independent Investigation of Complaints against the Police Policy Briefing Paper’ we identified that police investigators consistently: “i) Lack motivation to collect evidence from all witnesses or to gather available CCTV or other evidence in a timely manner; ii) Seem entrenched in a culture that tolerates or accepts police abuses, so tend to downplay or minimise unlawful conduct; iii) Interpret their job as picking holes in a complainant’s story rather than picking holes in the police version of evidence; iv) Tend to be uncritical of police accounts; v) Actively assist the police to frame a defence to the complaint;[2] vi) Use information obtained in complaint gathering to assist a prosecution of complainants; vii) Fail to question the police under criminal caution or for disciplinary purposes; viii) Fail to understand the law/Charter/Victoria Police Manual requirements and instead apply police logic or police “common sense” and understandings about “the way things are done” to police conduct (the issue of lack of understanding and application of rights under the Victorian Charter of Human Rights was noted in IBAC’s review); and viii) Intimidate or urge complainants to drop their complaint”.

Given these published findings concerning bias in the investigation process, it is deeply troubling that this issue does not warrant a mention in the IBAC review of Victoria Police handling of complaints.

Low Substantiation rates

An analysis of police complaint substantiation rates from 2000 to 2013 found that less than 10% of all complaints to police were substantiated, and less than 4% of all assault complaints are substantiated. In contrast, when courts are given the opportunity to assess these complaint allegations they regularly find they have substance – despite having been rejected by the police complaints system.[3]

The repeated failure by Victoria Police investigators to substantiate claims that are later found by the court to have merit is of serious concern, and is a notable omission from the audit process.

These markedly low rates of police complaint substantiation are also concerning in the absence of any mention of inherent bias in the investigation process. This infers that either IBAC did not examine the issue of inherent bias in their review process, or that IBAC are satisfied with the low current complaint substantiation rates – which itself raises serious questions about their competency or independence.

Corinna Horvath after having her nose broken in an unlawful police raid

IBAC recommendations

- Recommendation 1: “Develop a policy for local management resolution (C2-4) files including clear parameters for their use and communication with complainants and subject officers” and Recommendation 2: “Review the correspondence classification (C1-6) to determine if and when it should be applied.”

FKCLC support the first two recommendations, which are aimed at reducing delays in the complaints process. For most files there is a 90-day time limit for completion (this varies depending on classification), and we have encountered frequent cases in which Victoria Police have not complied with this time limit.

- Recommendation 3: “Implement a policy requiring PSC to attach a subject officer’s complete complaint history to all complaint files.

The attachment of complaint history is important in order to provide a thorough context for the complaint, the officer’s history and to identify any ongoing or repeat issues. It is essential that IBAC have access to a comprehensive complaint history in order to be able to examine historical behaviour of the officer in question.

- Recommendation 4: “Require investigation plans, investigation logs and final checklists to be completed and attached to complaint investigation files.”

The completion and collation of all complaint and investigation documents with the investigation file is important, particularly to address situations where there are technical defects with the complaint file, and to enable thorough and comprehensive review.

- Recommendation 5: “Require a Victoria Police conflict of interest declaration (form 1426) to be completed for all oversight and investigation files to ensure conflicts of interest are explicitly addressed and managed.”

We support this initiative to address conflicts of interest to ensure that those charged with investigating the complaint haven’t worked with the accused officers before. However, a focus on individual conflicts of interest is insufficient to address the broader issue of inherent bias and the need for independent investigation.

- Recommendation 6: “Review the system of determinations to reduce and simplify determination categories.”

Simplifying determination categories may reduce delay or administration issues and prevent files being lost or stalled.

- Recommendation 7: “Publicly release aggregated information on a regular basis (for example, in the Victoria Police annual report) on the number of complaints received, their classifications, determinations and recommendations to improve transparency and accountability for outcomes.”

The regular, public release of this overarching data about complaints received, and the outcome of these, is essential. The use of force or the use of coercive and invasive powers are a routine part of police members’ jobs, and measures to publicly release aggregated information are vital to monitor abuse of powers and the functioning of the complaints system.

As it stands, many complainants report being ‘locked out’ of the complaints investigation process. Complaints also fail because complainants are rarely given any opportunity to give feedback to an investigation before it is finalised. Nor are complainants routinely given access to the investigation reports into their claim. Indeed, it is currently the case that copies of investigation reports where a complaint was initially made to IBAC are now being regularly denied to complainants when they make FOI requests for them.

Beyond aggregated information at the general level, we recommend that individual complainants be provided with access to the report before finalisation. This would enable them to correct false assumptions, provide further information, witnesses or ideas. Further, as these reports frequently make negative comment about complainants, natural justice suggests they ought to have the opportunity to comment.

- Recommendation 8: “Require all formal and informal workplace guidance be recorded on subject officers’ professional development and assessment (PDA) plans to clearly outline performance or conduct issues and the actions taken in response to issues.”

This measure is useful to ensure that any ongoing conduct issues with particular officers are tracked to the management level, and any repeat or multiple complaints are monitored, with detailed actions in response.

- Recommendation 9 “Provide regional, departmental and command investigators with clearer information and training on the Victorian Charter of Human Rights to assist in identifying human rights that have been engaged by a complaint.”

Gaps in understanding of the Charter Rights has been identified as a gap in the current complaints process, and measures to inform and train regional, departmental and command investigators to identify and respond to breaches of human rights is vital.

The need for independent investigation of police complaints

The need for independent investigation of police complaints

“The abuse of force or power has a profound and detrimental impact on all those who experience it, their families and entire communities. It undermines safety, self-worth and belonging and it erodes faith in the institutions of democracy and the rule of law. Even minor excesses by Police can have a significant impact on the community.”

The abuse of police power already impacts most upon those who are more marginalised. The current police complaints system lacks integrity, transparency and independence. Of great concern to Flemington & Kensington Community Legal Centre, other Community Legal Centres and those who hear of complaints is that few people wish to proceed with a complaint once they understand that it will be investigated internally.

While the recommendations in the IBAC audit offer measures to improve the existing internal complaints process, these cannot and do not address systemic failures and inherent bias. The recommendations in IBAC’s review would not meet the requirements of the “Horvath test” – if Corinna Horvath’s assault by police occurred again today, these recommendations would not ensure justice nor come close to meeting the requirements of the UN Human Rights Committee’s decision on Horvath. The Victorian Government must, as a matter of urgency, properly resource a body separate from police to independently investigate all complaints made against police.

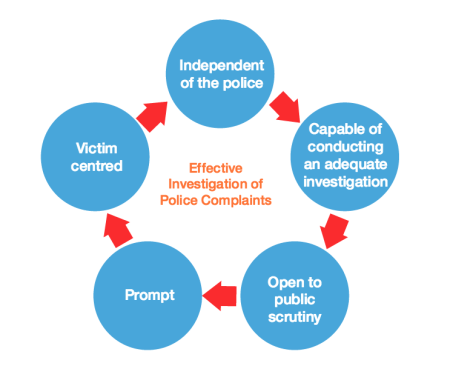

This body must be empowered to be independent of the police, prompt, open to public scrutiny, and victim-centred; enabling the victim to fully participate in the investigation and access information, and able to conduct effective Investigation of Police Complaints.

[1] https://www.policeaccountability.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CLCpaper_final.pdf

[2] See for example the investigation into the death of Adam Salter discussed in the Operation Calyx report, Police Integrity Commission, June

[3] See FOI results released to the FKCLC by Victoria Police on 10 October 2014 4 See FOI results released to the FKCLC by Victoria Police on 10 October 2014