A recent study highlights the range of data based techniques deployed by police forces across Europe with potential discriminatory impact on communities.

Researcher Adelle Ulbrick, from Melbourne University looks at this report and its implications.

The study Data-driven policing: the hardwiring of discriminatory policing practices across Europe, forms a comprehensive analysis and warning of the racial discriminatory effects that technology-based data collection and analysis and crime ‘prediction’.

In the report publish late 2019 by the European Network Against Racism (ENAR) authors Dr Patrick Williams and Eric Kind detail a “hardwiring” effect of racialised police responses based on certain data collection strategies.

New technologies such as facial recognition, video surveillance systems, body worn cameras, automatic number plate recognition and social media monitoring are used to collect data which is then used to create and analyse trends in crime. These trends become the foundation for policing practices that aim to predict and prevent people who are likely to commit crime and in places where crime is likely to occur. As detailed in this report, these technologies have the propensity to codify racialised police responses and skew predictive policing tools in a way that has an effect similar to that of racial profiling practices.

In the forward of the report, Karen Taylor, Chair of ENAR writes:

“We, as activists, as anti-racist organisations, and as racialised communities in Europe, know too well what it means to be over-policed and under-protected.

Still, in 2019, we feel the need to evidence racial profiling, to contest narratives placing us as a threat to ‘security’ and essentially to unsettle presumptions as to our criminality. We are still mastering the techniques with which we contest over-policing, brutality and racial profiling. We must now contend with another challenge. When law enforcement resorts to new technology to aid their practice, we find ourselves at further risk”

These predictive policing tools negatively and disproportionately impact ethnic minority communities in three main ways.

1) Firstly, the use of new technologies exacerbates the existing issues of surveillance. Data collection and analysis is focused on communities already experiencing disproportionate over-policing, meaning that they are more likely to feel the effects of these tools.

2) Secondly, technical limitations, such as misidentification in facial recognition software, will increase the likelihood of discriminatory policing practices, such as the rate of stop and searches experienced by ethnic minority community members.

3) And finally, predictive policing systems have been based upon data collected through ethnic profiling and racial policing strategies that disproportionately represent certain geographical areas and ethnic minority communities as being “risky” and in need of increased police and law enforcement responses.

The use of new technologies drives over-policing in a cyclical way whereby recorded data reinforces the perception that certain communities are worthy of surveillance, and therefore community members are more likely to come into contact with police, which in turn increases the likelihood of being caught committing an offence, which then contributes to the recorded data on crime in the given community. Ethnic minority communities and groups are therefore more likely to come into contact with law enforcement following an offence not because they are more likely to commit an offence, but simply because they are more likely to be under higher police surveillance.

The use of new technologies drives over-policing in a cyclical way whereby recorded data reinforces the perception that certain communities are worthy of surveillance, and therefore community members are more likely to come into contact with police, which in turn increases the likelihood of being caught committing an offence, which then contributes to the recorded data on crime in the given community. Ethnic minority communities and groups are therefore more likely to come into contact with law enforcement following an offence not because they are more likely to commit an offence, but simply because they are more likely to be under higher police surveillance.

The racial disparity that is already evident in policing operations is further exacerbated when these interactions are employed under the premise of data collection and pre-emption.

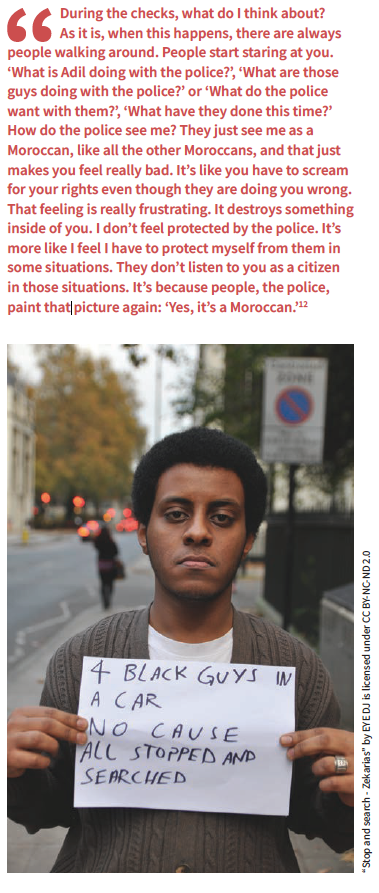

Across Europe, people of African, Arab, Asian and Roma descent, as well as religious minority communities have more encounters and contact with law enforcement agencies than people from the majority white populations. The racial disparity in policing across Europe is evidenced in the higher rates of stop and search requests, prosecution of offences, the type and severity of punishment and higher imprisonment rates for minority communities despite committing criminal offences at similar, if not, lower rates than the majority populations.

It is important to note that being subject to over-policing and contact with law enforcement such as in stop and search requests is not indicative of, or a measure of, criminality. Rather, it reflects the states’s formal response to certain minority groups to the wider community, which shape public perceptions of crime and criminality.

Minority ethnic groups and communities are subject to racial criminalisation, whereby narratives of suspicion, risk and assumptions of criminality are based on certain traits and characteristics rather than by criminal behaviours. By being labelled as “risky”, instead of as being “at risk”, this racial criminalisation is justified and further perpetuated by police responses and operations. Racial criminalisation normalises the over-policing of ethnic minority communities whilst simultaneously reinforcing the majority community perceptions and assumptions of risk and criminality associated with certain ethnic minority group members.

The normalisation of ethnic minority community members’ contact with police acts as an extension of racial profiling; “‘well it’s normal, I am Gitano and that’s why they stop me.’ There is no documentation that can show that they stopped you for a racial profile if they say it’s routine, security, suspicion”. Although the practice is not a direct form of racial profiling, the nature of the suspicion and risk and the unintended consequences of what is ultimately a discriminatory practice, functions in the same way and produce a similar racialised and discriminatory effect in policing practices.

This racial criminalisation is further illustrated by public perceptions and law enforcement attitudes and responses to the issue of “gangs”. There is no clear definition of “gangs” and “gang behaviour”, however they have increasingly become racially fuelled terms, to the extent that law and order responses have become similarly racialised. In France, young people from immigrant backgrounds were significantly over-represented in the youth justice system and police operations targeted predominantly immigrant and ethnic minority groups. In London, approximately 78% of those recorded to the police gang database are from a minority ethnic background. Law enforcement responses in the context of the “gang” issue have been racialised to the extent that the word “gang” comes to exclusively refer to ethnic minority group members and certain communities become criminalised.

In Denmark, overtly racialised policing practices perpetuate the racial criminalisation of certain communities. The geographical location of where the offender lives dictates the severity of their punishment. The penalty is doubled for offenders from areas that have high proportions of minority group members. The practice comes to punish ethnicity and criminalises communities with a high proportion of a minority population, rather than basing the punishment exclusively on the crime that has been committed. The “harsh penalty zones” are defined based on certain social criteria, which targets and disproportionately impacts ethnic minority communities instead of targeting geographical areas of high levels of detected crime. The use of these harsh penalty zones therefore acts to criminalise ethnic minority community members and contributes to the racial criminalisation of such communities.

Technology has an impact on policing practices and predictive tools. Technology is neither neutral nor objective. Technologies are developed based on human interactions which perpetuate socio-cultural inequalities and biases and act to disproportionately target minority communities. Assumptions of risk, suspicion and criminalisation all impact the ways in which technology is developed, moderated, implemented and evaluated. The propensity to detect, predict and prevent crime is therefore influenced by racially discriminatory procedures that have been hardwired and embedded into the predictive policing technology and analytical tools. The degree to which these technologies can analyse and predict trends in crime is dependent on the data collected. When this data is collected based on racialised policing practices, the resulting predictive tools are inherently racialised and act to perpetuate an over-policing and surveillance of ethnic minority communities and groups.

As evidenced in Europe, data-driven technologies influence predictive policing strategies, which disproportionately impact ethnic minority communities and reinforce racial criminalisation.

There is a clear need for a greater level of law enforcement transparency, care in data collection techniques and understanding of the limitations and impacts of new technologies and data based analytical tools in predictive policing practices.

‘Predictive’ policing systems are increasingly being implemented by police forces around the world such as the UK’s Gangs Matrix or the Netherlands’ top 600 and top 400, also known as Pro-Kid [1].

In April 2020, the Los Angeles Police Department announced it was dumping elements of a controversial predictive policing program called PredPol which local campaigners accused of magnifying racial bias. Hamid Khan, the founding organiser of the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, which campaign against the program for many years has said that the LAPD’s decisions to scale back on predictive policing and stop using words like “dosage” were “sanitizing” programs that would continue to target black and Latino residents. “There is no kinder, gentler predictive policing system. It is racist.”

In Australia, the Policing Young People in NSW report, authored by Vicki Sentas (UNSW Law) and Camilla Pandolfini (Public Interest Advocacy Centre), found that young people on what is called the Suspect Targeting Management Plan (STMP) experience “inappropriate forms of over-policing disproportionate to the future risks they are alleged to pose to society”, and concluded that NSW Police should not be exposing any young people to the program. The research also found that the STMP disproportionately targeted young Aboriginal people. In February 2020, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC), NSW’s police oversight body, published an interim report into STMP and its impacts on children and young people but only made minor recommendations.

The Police Accountability Project is continuing it research into data-driven, predictive policing programs by Victoria Police.

Williams, P. & Kind, E. (2019) ‘Data-driven policing: The hardwiring of discriminatory policing practices across Europe’ is available at: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/624446/1/data-driven-profiling-web-final.pdf

Williams, P. & Kind, E. (2019) ‘Data-driven policing: The hardwiring of discriminatory policing practices across Europe’. Available at: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/624446/1/data-driven-profiling-web-final.pdf